Amy Archer-Gilligan had a knack for caring for the elderly and opened her own private nursing home in 1907 in a large brick house in the town of Windsor, CT, with her husband, James Archer (later on, we’ll redefine knack a bit). James died three years later, leaving behind a nice insurance settlement, and Amy remarried in 1913 to Michael Gilligan, who died three months after the ceremony, leaving her with enough money in the will to continue her nursing home business. So that’s kind of a happily ever after (later on, we’ll redefine happily ever after a bit). In hindsight, many believe that her hyphenated surname was less of a moniker and more of a hit list.

Meanwhile, over the course of 10 years from the time she opened the Archer Home for the Elderly and Infirm, some 60 people died in the house, most of them after 1910. Seems like a high turnover rate, but old people die, right?

Yup, especially if they are fed arsenic.

Eventually, the body count got too high to ignore, corpses were exhumed and tested, purchase records of toxic substances were examined, and Archer-Gilligan was indicted on five counts of poisoning, including that of her second husband.

Only one count stuck, a resident of the home, but many believe that the stats on the back of her official serial killer card might be grossly underestimated and that most of the 60 deaths were due to her arsenic-tipped scythe.

Some people say her motives were economical. Every empty bed in the house was the chance for a new customer, and money makes the retirement home go round. Of course, murder’s never purely economical. Especially serial murder. You also have to be absolutely demented (no redefining the term, there).

Archer-Gilligan was sent to prison, and then moved to a psychiatric hospital, where she died in 1962 in her late 80s. She never got herself a slick serial killer name, but her nickname in real life was “Sister Amy” due to her standing in the community, and that’s as good a serial killer name as anybody’s ever come up with.

Oh, and this is what she looked like.

Two major memorials still stand to her atrocities. The first is the murder house itself, which sits in the idyllic town of Windsor at 37 Prospect St. The large brick house, like the other large houses in the neighborhood, has since been turned into apartment units, and the way it looms there seems to be the architectural equivalent of whistling innocently, with nothing really to give a clue as to the gentle violence that happened under its roof.

A strip of discolored brick that runs the width of the façade of the house reveals the location of what was probably an overhang of some sort and one of the second-floor windows has been bricked solid in a permanent wink. But other than these two changes, most of the large house hasn’t changed. I assume fewer people die there these days, of course.

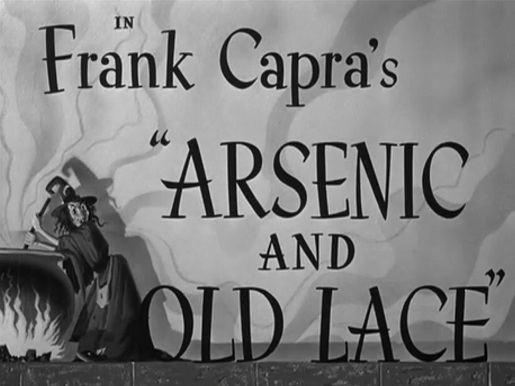

The other, more well-known testament to Sister Amy’s crimes is Arsenic and Old Lace. The story started out as a Broadway play in the early 40s, but gained even more attention as a Frank Capra movie released in 1944 (while Sister Amy was still alive) and starring Cary Grant, Peter Lorre, and a Boris Karloff look-a-like, a role Boris Karloff himself played for the stage version.

In the story, which takes place on a single Halloween night, the nursing home has been turned into a pseudo-boarding house, Windsor has been turned into Brooklyn, and Archer-Gilligan has been turned into two old aunts named Brewster with a reputation for being the nicest old spinsters that anybody would ever have the pleasure of being buried by.

In fact, they’re so dedicated to kindness that they end up putting old, lonely men out of their misery by lacing homemade elderberry wine with a mixture of arsenic, strychnine, and cyanide, all meted out with the care of an old family recipe and killing about a dozen men in the course of their polite reign of terror.

Actually, the entire Brewster family is a bit batty. Besides the two killers, there’s Teddy, who thinks that he’s Theodore Roosevelt, and Jonathan, a sadistic serial killer of the more classic sort who escapes from prison with Peter Lorre and holes up in his childhood home.

What happens next is a comedy of corpses, often over the top and just as often charming and witty, if stretched too long at two hours and centering on a miscast and mugging Cary Grant, the one saniac in the family.

Overall, the movie makes light of murder, mental illness, loneliness, and the Panama Canal. It’s a good time that’s made even better knowing it was based on the life of an actual serial killer, one whose house you can still trick-or-treat at.

Nobody will ever make a movie about your good deeds.